When you type, do you insert two spaces after a period? Some netizens are up in arms because Microsoft Word now flags double spaces after a period as errors. If you don’t understand the concern, it’s because many people were taught to type two spaces after a period that ends a sentence (well, at least people who learned keyboarding on machines called typewriters). Typewritten pages use monospaced fonts. Two spaces after a period can make a typewritten page more readable.

Decline of the Space

Typographers have always been able to use spaces of varying widths. Style guides for book publishing before the 20th century recommended dividing sentences with slightly wider spaces than the spaces that divide words. Today, most books and newspapers use single spaces after periods, though it’s difficult to know whether this is from laziness, economizing on the cost of production, or an evolving consensus about readability. Most style guides seem to have settled the issue in favor of a single space. Still, netizens rage.

Tex, the first popular digital typesetting system, outputs extra space after a period ending a sentence. Almost anyone who has taken the time to learn Tex will insist that the adding an extra space after a period makes a more elegant page.

How about web pages? Should web browsers display extra space between sentences? If you type two spaces after a period in an HTML file, should the browser preserve both spaces? In 1993, in the web’s early days, the developers of web browsers had to decide.

How the Web Was One

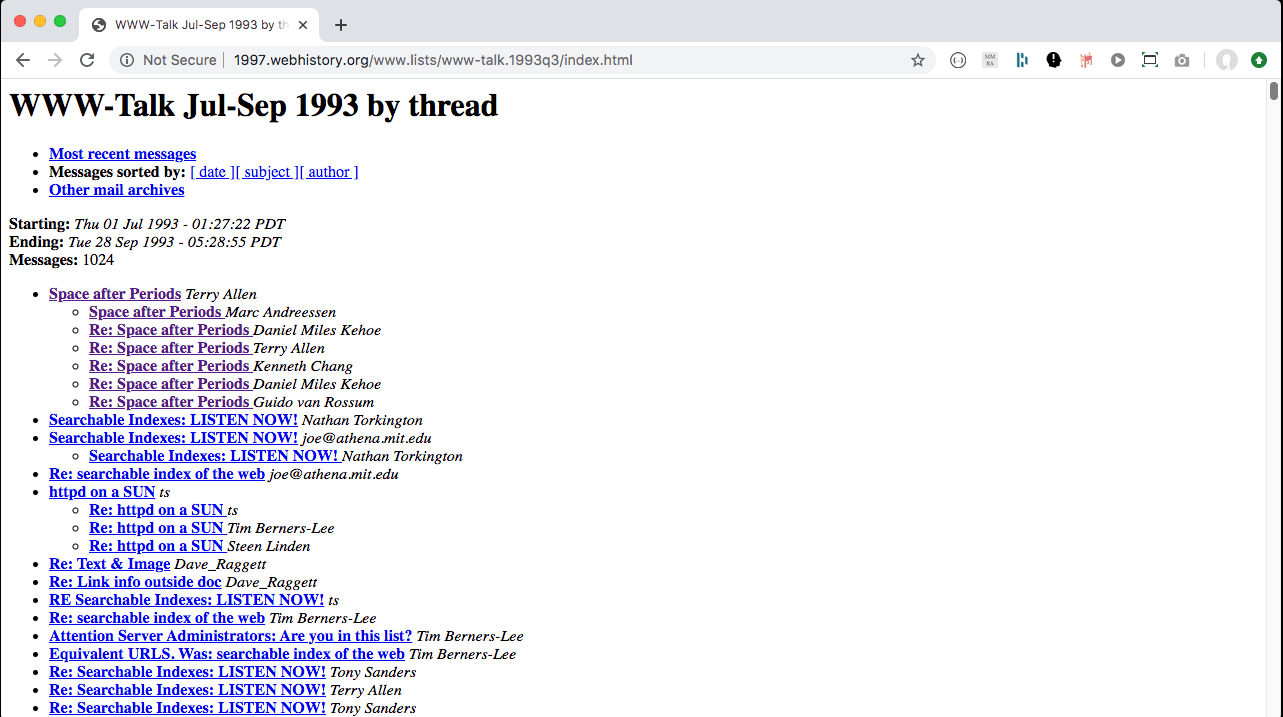

I was active on the www-talk mailing list in 1993. In July, in the thread “Space after Periods,” Terry Allen (an editor at O’Reilly) wanted rendered HTML documents to follow Tex conventions with extra space after a period.

Having worked at a few jobs in publishing and thinking that perhaps I knew a thing or two, I proposed that, “A WWW document (which uses proportional fonts) should have the same space between sentences as between words” and cited as authority “Words into Type” and the “Chicago Manual of Style.” in 1993, “WIT” and “Chicago” set standards for publishing much like RFCs do for the Internet.

Terry Allen and I engaged in some snarky backbiting, then Ken Chang of NCSA Publications said he preferred “‘one space fits all’ as writers of HTML really shouldn’t need to know the fineries of typography.” Marc Andreessen (still at NCSA in 1993) pointed out browser developers couldn’t be expected to implement the syntactic analysis required to distinguish the end of sentences from inter-sentence periods. Finally Guido van Rossum (the developer of the Python programming language) complained that, “extra space after a sentence… is mostly propaganda by Knuth and Kernighan (TeX and troff)” and implored, “Let’s keep HTML simple!” You may know that Python is unique among programming languages in treating whitespace as significant. At the time, I hadn’t yet learned to use Python (it was still pre 1.0) and didn’t know that Guido van Rossum had strong feelings about the significance of whitespace.

In the end, we ended up with browsers putting a single uniform space between sentences (as you can see on this page). If you don’t like the way that browsers handle spaces between sentences, you can blame me (and Ken Chang and Marc Andreessen and Guido van Rossum).

Ideology in Everyday Life

Looking back, I wonder if browser developers could have applied the algorithms that Tex uses and perhaps web pages would look slightly more elegant.

We take for granted the world around us. Web browsers work a certain way; web pages display the same space between sentences as between words.

We forget that many things we take for granted are the product of a social process (or “social practice” as Mao Tse-tung famously said). In this case, something you probably took for granted (and probably never even thought about), was the product of a brief discussion in the summer of 1993 among developers who each had their own beliefs about what was right and good.